Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1768)

Exploring the Opinion of Bulgarian Dentists and Students of Dental Medicine About the Role of Communication in the Treatment of “Difficult Patients” in the Dental Practice Volume 1 - Issue 5

Vesela Aleksandrova*

- Dental practitioner, Germany

Received: October 10, 2018; Published: October 22, 2018

Corresponding author: Vesela Aleksandrova, Dental practitioner, Germany

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2018.01.000121

Abstract

Communication is a common subject in a variety of scientific disciplines and in medicine it means building a doctor - patient relationship, listening, gaining trust, empathy [1-3]. In recent years the reasons have been investigated why a patient follows a given dental therapy. The role of communication used during dental treatment - verbal and non-verbal - is the basis of these studies. Often in dental practice there are the so-called “difficult patients”. Their treatment is defined as a stress factor in everyday practice and a challenge for the dentist [1]. The dentist requires a special approach with these types of patients in order to have strong communication with the patient and to facilitate better therapeutic results and satisfaction with the treatment [3-5]. The aim of this study is to investigate the opinion of Bulgarian dental practitioners and dental students regarding the role of communication in the treatment of “difficult patients.”

Materials and Methods

A survey among dentists from different ages and different specializations was conducted at the 15th International Scientific Congress of the Bulgarian Dental Society, 11-14. 06. 2015. 150 questionnaires were handed out, 132 were filled out. The questionnaire was based on a standardized questionnaire from a similar survey at the University of Ulm, Germany [6]. The study was also conducted among students at the Faculty of Dental Medicine, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, divided into 2 groups: the first included students from second year (before passing the training course in communication in the dental practice); the second group included students from the 3rd and 5th years (after the communication module). Out of 300 questionnaires, 136 were completed by the first group and 138 by the second group. The questionnaire included 25 questions: the first part contained questions related to socio-demographic characteristics of the research contingent, the second contained questions about communication techniques involved in the university education and assessment of the role of education and social environment on the relationship between patient and care provider. Some of the questions were based on the dentists’ and students’ own experience. They examine how often they encounter the so-called “difficult patients“, which patient groups they classify as “difficult” and how they manage to treat them. The questions were assessed with the Likert scale. The Mann- Whitney U test, alternative and graphical analysis, was utilized for the statistical analysis.

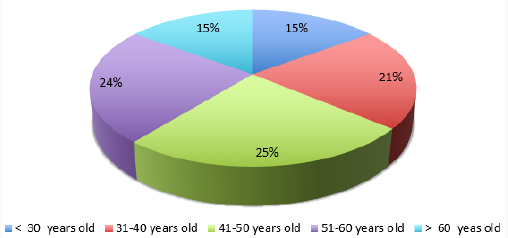

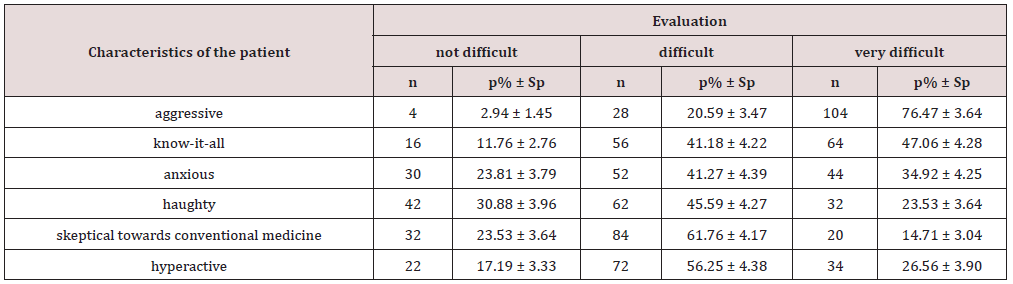

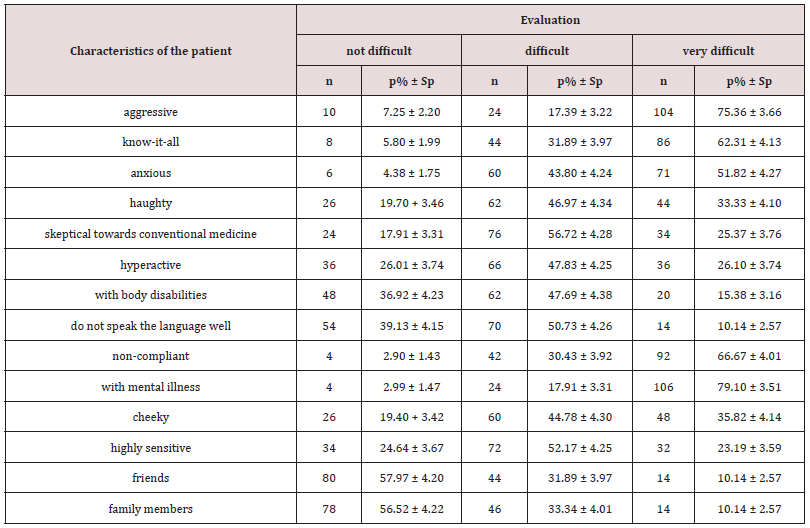

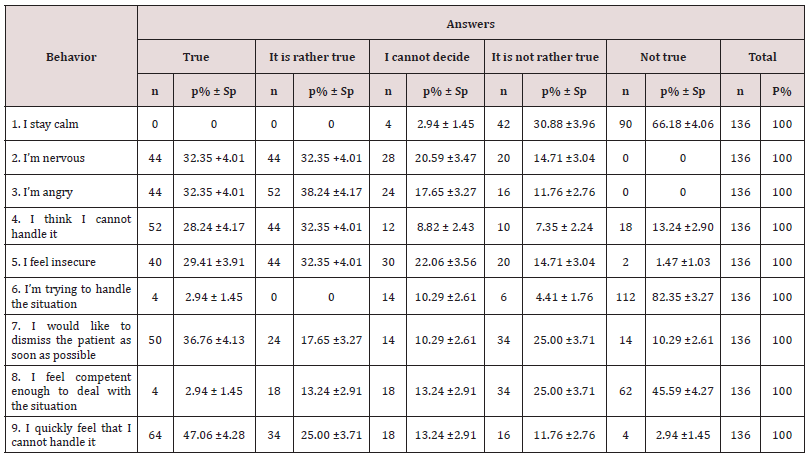

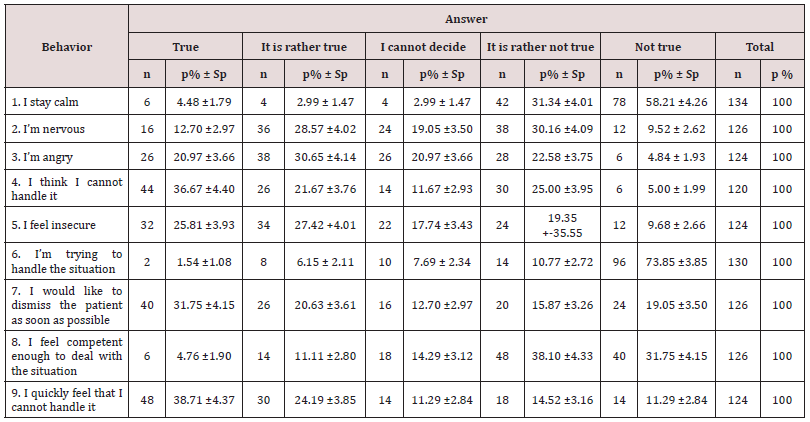

Results

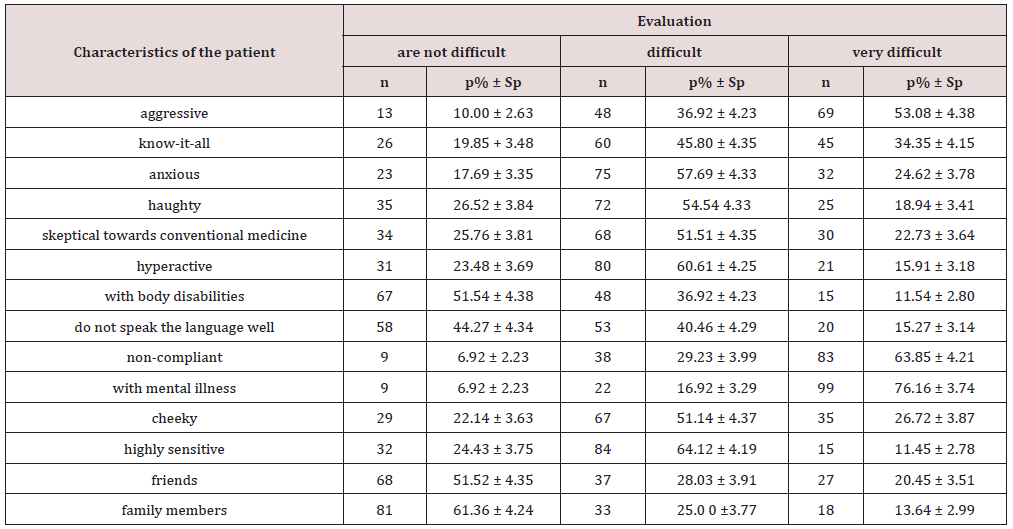

In the dentists‘ group 74 (56.06 % ± 4.32) were women and 58 (43.93% ± 4.32) men with similar shares in the different age groups (Figure 1). In the first group of dental students 104 (76.47% ± 3.64) were women and 32 (23.53% ± 3.64) men. In the second group of 138 students 102 (73,91% ± 3,74) were women and 36 (26,09% ± 3,74) men. 79.55% of the dentists assessed the conversation prior to treatment as “very important” and 66.67% identified the possession of communication techniques as “very important”. The results in the students‘ group were similar - 79.42% before and 76.81% after communication training define the importance of talking to a patient as “very important”; 58.82% before and 59.42% of the students after learning communication techniques reported that having special communication skills is “very important”. The survey among the dentists included the question: “Which patients do you define as extremely difficult”. They were offered to choose from 14 specific groups of patients, assessed with the three-point Likert scale as “ not difficult “, “ difficult “ and “ very difficult “ (Chart 1). More than one answer was possible. 99 of the dentists (76,16% ± 3,74) considered as “very difficult” patients with mental illness, followed by non-compliant patients (n = 83, 63.85% ± 4.21) and aggressive patients (n = 69; 53.08% ± 4.38). It turns out that easiest to treat are family members (n = 81; 61,36% ± 4,24) and friends (n = 68; 51.52% ± 4.35). The results of the students are presented in Chart 2 & 3. It turns out that there is a statistically significant difference in some of the categories, comparing the results before and after communication training: after the training the share of students who define anxious patients as “very difficult” increases from 34.92% ± 4.25 to 51.82% ± 4.27 ( p <0.01; u = 2.95). Patients with disabilities are, according to 4,41% ± 1,76 of the students before training, “very difficult”, after training - 15,38% ± 3,16 (p <0,01 ; u = 2,56) . Half of the students surveyed before training noted that non-compliant patients are “very difficult” and their share after communication training rises to 66.67% ± 4.01 (p <0.05; u = 2.24). There is no difference in the responses about aggressive patients - before training 76,47% ± 3,64 identify them as “very difficult “, after training - 75.36% ± 3.66 . Students were also given the opportunity to share their opinion about their own behavior towards the socalled “difficult” patients before and after communication training. Nine common reactions were defined in the questionnaires (Chart 4 & 5). After communication training, the share of students who responded with “nervous” and “angry” significantly decreased, and the share of respondents with “stay calm” slightly increased.

Chart 1: Frequency of the dentists‘ responses to the question: “Which patients do you define as difficult” according to the characteristics.

Chart 2: Frequency of the students’ responses to the question: “ Which patients do you define as difficult” according to the characteristics before attending communication course.

Chart 3: Frequency of the students’ responses to the question: “Which patients do you define as difficult” according to the characteristics after attending communication course.

Chart 4: Students’ behavior during a conversation with “difficult patients” before communication training.

Chart 5: Students’ behavior during a conversation with “difficult patients” after communication training.

Discussion

Communication in the dental practice is a relatively new topic in Bulgaria. The present study shows parallels with world trends in feminization of the profession in the group of dentists and students in Bulgaria [7-10]. It underlines the importance of a thorough conversation and the positive attitude of the Bulgarian respondents towards the topic in accordance with international development in this field [11-13]. A major challenge in everyday practice is the treatment of aggressive patients [14]. Aggression can be caused by fear or stress and occurs spontaneously. Half of the dental practitioners define these patients as “very difficult”, while the share of students is relatively constant before and after communication training - about 76% (p <0.001, u = 3.58). This can be explained by the students‘ lack of experience and the steady and routine way of working of the dentists. For about two-thirds of doctors and students in both groups non-compliant patients are defined as “very difficult”. The patient’s duties are to observe proper oral hygiene, carry orthodontic appliances or bands, keep dental appointments and prescribed treatment. Failure to comply with these obligations leads to unsuccessful treatment and dissatisfaction, making these patients “difficult”. Most dentists and students in both groups report that patients with mental illness are “very difficult”, which is understandable, because their successful treatment requires individual and adequate approach, as well as more time. The share of students after communication training, defining anxious patients and patients with a disabilities as “very difficult” is increasing. This shows that with the acquisition of clinical experience, students’ awareness about the challenge these patients represent is increasing. An interesting fact is that according to Bulgarian dentists and students, the easiest patients to treat are friends and family members. It is recommendable to treat these two patient groups like the rest of the patients, ignoring the emotional component that could disrupt the objectivity of medical expertise [15,16]. In order to gain more information about students’ behavior in a clinical setting, the students in the questionnaires were given the opportunity for self-assessment of the behavior during a conversation with “difficult patients”. The fact that after communication training students feel more secure (p <0,05, u = 1,96) shows that communication skills in the dental practice are not given, but rather a series of skills that can be formed by continuous training. They improve the dentists’ confidence during treatment and the effectiveness of their work and have a positive influence on the satisfaction of the patient [17,18].

Conclusion

This study confirms the importance of communication skills in the dental practice during university education and in the treatment of “difficult patients”. The treatment of various patients in everyday practice requires adequate communication skills, tailored to the individuality of each patient. Only in this way can the dentist build a strong environment in the dental practice and trust between the dentist and the patient [19-21].

References

- Cooper CL, Mallinger M, Kahn RL (1980) Dentistry: what causes it to be a stressful occupation? Appl Psychol. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, USA 29(3): 307-319.

- Gerbert B, Bleecker T, Saub E (1994) Dentists and patients who love them: professional and patient views of dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 125(3): 264-272.

- Langewitz W, Eich P, Kiss A, Wössmer B (1998) Improving communication skills - a randomized controlled behavioral intervention intervention study for residents in internal medicine. Psychosom Med 60(3): 268.

- Haak R, Rosenbohm J, Koerfer A, Obliers R, Wicht MJ (2008) The effect of undergraduate education in communication skills: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Dent Educ 12(4): 213-218.

- Ramirez A, Graham J, Richards M, WM Gregory, A Cull (1996) Menal health of hospital consultants: the effect of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet 347(9003): 724-728.

- (2013) Lauf an der Pegnitz Gebhard FRS. The importance of teaching in interviewing from the point of view of dentists and students of dentistry. University of Ulm, Germany.

- ADA (1993) Distribution of Dentists in the United States by Region and State. Health Policy Institute.

- Brecht, JG, Meyer, VP, Micheelis W (2009) Prognosis of dentist numbers and needs and dental services by the year 2030.

- McKay JC, Quiñonez CR (2012) The Feminization of Dentistry: Implications for the Profession. J When Dent Assoc.

- Stewart FMJ, Drummond JR (2000) personal view: Women and the world of dentistry. Br Dent J Nature Publishing Group 188(1): 7-8.

- Wagner J, Arteaga S, D Ambrosio J, Hodge CE, Ioannidou E, et al. (2007) A patient-instructor program to promote dental students’ communication skills with various patients. J Dent Educ 71(12): 1554-1560.

- Woelber JP, Deimling D, Langenbach D, Ratka Krüger P (2012) The importance of teaching communication in dental education. A survey amongst dentists, students and patients. Eur J Dent Educ 16(1): 200- 204.

- Janke F, von Wietersheim J (2009) Anxiety wants to be present at the dentist-a questionnaire exam to patients and their dentists. Dtsch Dentist Z 64(7): 420-427.

- Cooper C (1980) Dentists under pressure: a social psychological study. Wiley.

- Gold KJ, Goldman EB, Kamil LH, JD Sarah Walton, Tommy G Burdette, et al. (2014) No Appointment Necessary? Ethical Challenges in Treating Friends and Family. N Engl J Med Massachusetts Medical Society, USA 371(13): 1254-1258.

- Schutz SM, JG L, CM S, Almon M, Baillie J (1994) Clues to patient dissatisfaction with conscious sedation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 89(9): 1476-1479.

- Kurtz S, Silverman J, Draper J (2005) Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine. (2nd edn) Radcliffe Publishing Co, UK .

- Oh J, Segal R, Gordaon J, et al. (2003) Retention and use of patientcentered interviewing skills after intensive training. Acad Med (76): 647-650.

- Savova Z, Sidzhimova D (2008) Psychology training of the communication of dental specialists. In: Management and education.

- Zwart E, Gresnigt Bekker COVM (2017) Preventive dentistry 2. The force of habit and the change to a healthy oral behavior. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd 124(1): 28-33.

- Koehler A, Gruender M (2012) Online marketing for the successful dental practice. (2nd Edn). Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...