Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1768

Review Article(ISSN: 2641-1768)

4.5-5.5-Year-old Gifted Students: Findings from the 2004 Cohor Volume 1 - Issue 4

Hanna David*

- Tel Aviv University, Israel

Received: September 25, 2018; Published: October 04, 2018

Corresponding author: Hanna David, Tel Aviv University, Israel

DOI: 10.32474/SJPBS.2018.01.000117

Abstract

We are all aware of many beliefs about the superiority of girls over boys among the very young: girls are expected to speak earlier than boys, to adjust to social requirements better and at an earlier age than boys, and to function better in activities demanding fine motor skills. The question whether this is also the case among the gifted has remained unsolved, in spite of the fact that the study of gifted kindergarten students has been a most intriguing one for researchers for many years. In this study we have challenged the general belief of superior female development among pre-school children, by showing that participation rate of girls among gifted pre-school children is lesser than among older children. Girls who were accepted to the gifted courses at The Erika Landau Institute for the Promotion of Creativity and Excellence had lower cognitive abilities than boys, in spite of the fact that they hardly reached a 30% participation rate. In addition, girls did not achieve significantly higher evaluations in either of these parameters: thinking quality, openness, social acceptability, self-confidence, persistence, attitude to problem-solving, and involvement level in conversations in the final evaluation of the performance in Institute’s activities. This study aims to examine if we can predict the success of pre-school children in the first course they take at the Erika Landau Institute for the Promotion of Creativity and Excellence, Founder Dr. Erika Landau, and what is the validity of such prediction. Success level at the end of the one-semester “creative thinking” course is defined by the instructor’s final evaluation of the students’ performance. The components we take into consideration as potential success predictors are The IQ scores of the children, the verbal evaluation of the examiner, the written information in the parents’ questionnaires, and the summary of the counselor who interviews the student accompanied by at least one parent. The study of connections between cognitive, social, psychological, and emotional abilities of gifted pre-school children and their performance at the end of the first intervening course at the Institute must take into account many of the variables relating to familial and environmental components, as well as to cognitive and personal traits. In the present study we used only some of these variables, in order to give appropriate answers to 6 research questions.

Overview of the Current Research

Studies dealing with many aspects of gifted pre-school children has been written for many years. A large majority of them has been qualitative, mainly because at this age-group it is quite complicated for the researcher to form large enough groups for a quantitative study. Many of the quantitative studies that have been completed focus on social/psychological characteristics of the gifted child. For example: Rogers [1] has compared developmental characteristics of gifted and regular 77 pre-school children. He found that contrary to the common belief that parents tend to think their young child is gifted, parents of the gifted had, in many cases, underestimated the abilities of their gifted children. Rogers (ibid) also found that the gifted were different from regular pre-school children in psychological as well as cognitive and social aspects, such as alertness, attention span, memory, perfectionism, imagination, creativity, and many more characteristics. Smutny [2], on the other hand, had covered, in her 41-chapter book, five aspects of intervention with gifted pre-school children: identification, special populations, parenting, meeting social and emotional needs, and creating effective educational experiences. This work is no doubt very useful for educators and parents who need instruction for dealing with young gifted children, but in none of these chapters can we find actual findings of any study concerning evaluation of an intervention program when taking giftedness level into consideration.

Many more studies have been done on gifted kindergarten students since the early 90ies. Louis & Lewis [3] have studied gender differences in identification among 118 pre-school children; Robinson et al. [4], studied mathematical giftedness in this agegroup; Schneider & Daniels [5] studied 29 gifted preschoolers and compared some of their socio-metric characteristics to those of regular children; Smutny [2] has studied educators of gifted young children and came to the conclusion that many of them still emphasized the importance of socialization rather than their educational needs, believing young students should not be pressured into high achievement. Pfeiffer & Petscher [6] offered a scale for identifying young gifted children; while Walsh [7] wrote a dissertation about the needs of young gifted children and how to fulfill them. Many Studies have been written about this subjects, some by Hanna David [8-12] and many more by others. However, none of these works has examined connections between the children’s abilities, as measured by the WPPSI results, and interviewers’ opinions, based on counselors’ interviews done before starting a gifted course, and the success evaluation of the course, written by the instructors at its end. This study intends to answer some questions regarding such potential connections.

The Research Questions

a) What was the girls’ participation rate among pre-school children starting their studies at the Institute in February 2004 and October 2004? Was this rate similar to that of the whole cohort of 2003? Was it similar to the participation rate of girls in other years?

We have already found Landau & David [12] that the percentage of girls in the Institute’s population increased from about 30% in 1982 to almost 40% in 2003. We have also shown (David, in press) that in the 4.5-5.5-year-old age group girls’ rate was much higher both in 1993 (42.5%) and 2003 (~45%).Thus, we would have expected that in 2004 the participation rate of girls would not decline under 40%. We shall hereby see if this was indeed the case.

b) Was there a significant age gap between the mean age of boys and girls?

c) In previous studies of gifted kindergarten students, it was found that girls outperformed boys in verbal abilities and social maturity. As many parents, as well as kindergarten teachers, tend to recommend children for giftedness examinations when they are perceived as mature enough to take them, it is interesting to see whether the girls in our group were perceived as mature enough for taking these courses when younger than boys.

d) Were the WPPSI scores of the girls in our cohort higher than those of boys?

e) We could have expected that because of underparticipation of girls the girls that have taken the “creative thinking” course would rate higher than the boys, whose proportion in the cohort was significantly higher than would have been expected. We shall hereby find if this was indeed the case.

f) Was there a gender different in the magnitude of the gap between the mean verbal and performance IQ’s?

g) As we know, a large gap between the verbal and the performance IQ might be an indication of immaturity. It would be important to know if such a gap had been observed, and thus learn more about potential differences in emotional maturity of both genders.

h) What were the correlations between the results of the WIPPSI tests taken before the beginning of the “creative thinking” course, and the instructors’ evaluations at its end?

i) In studying gifted children, the results of an IQ test are considered a good predictor of success in activities that require high level of cognitive abilities. Thus, it is important to know if this assumption is also valid for kindergarten gifted children participating in a creative thinking course, and to what extent.

j) Was there a significant difference in the success rate of girls and boys at the end of the first course?

Pre-school girls are, on the average, more developed than boys in verbal, social, and fine motor abilities Hedges & Nowell [13]; Ronald, Spinath, & Plomin [14]. A high evaluation at the end of the creative thinking course meant that the participant had done well regarding cognitive abilities: thinking quality, attitude to problemsolving such as thinking abilities and problem solving; social abilities: social acceptability and Involvement level in conversations; and psychological aspects: openness, self-confidence, persistence, and direction of aggression. It will be important to see whether the alleged superiority of girls both in verbal abilities that help reaching higher cognitive abilities and social-psychological ones will be translated into higher evaluation of girls.

The Method

Examinees

We have studied 100 kindergarten students-71 boys and 29 girls-who had completed the “creative thinking” one-semester course at the Institute in June 2004 and January 2005. The children participated in 10 learning groups, instructed by 6 instructors: 5 women and one man. One of the instructors taught 2 classes in each of the semesters, another taught 2 classes during one semester, and all other 4 taught just one class. The maximal number of students registered to one course was 14; the minimal-10. 15 of the registered students either did not start studying or dropped out after a few meetings; only in one class no drop-out was informed. Thus, at the end of the semester the number of students per class ranged between 7 and 13, with an average of 10.

Tools

The research tools were: 1. The personal files of the students filled by their parents upon registration to the Institute; 2. The summary of the interviewer; 3. The instructors’ evaluation at the end of the semester.

The Content of the Personal Files

Each student’s file contains a parents’ questionnaire as well as the following educational, biographical, and demographic information:

a) Numerical result of the WSSPI examination (verbal,

performance, and total), taken either at the Institute or

elsewhere. In addition, verbal evaluations of the examiner for

emotional maturity evaluation of each child;

b) Gender

c) Age

d) Family members learning (or learnt) in the Institute [e.g.

parents, siblings]

e) Number of siblings, their age and gender

f) Birth-order

g) The gender of the elder sibling/s

h) Father’s and mother’s profession

i) Father’s and mother’s education

j) Father’s and mother’s age

k) The language[s] spoken at home

l) Year of immigration to Israel (if not Israeli-born)

m) Single-or two-parent family

n) Father’s and mother’s origin

o) Number of siblings of each parent

p) Level of reading

q) Level of religiosity [not-religious, traditional, religious,

Ultra-Orthodox]

r) Special academic, physical, or emotional problems

The parents’ questionnaire was a 3-page form parents of the children who register to the Institute had to fill. It included questions on child-parents’ interactions, as well as educational viewpoints and opinions on various subjects. In addition, each parent was asked to fill the “additional remarks” rubric at her or his wish.

The Interviewer’s Summary

Before choosing the first course each child had to be interviewed at the Institute accompanied by at least one parent. The interviewer filled, during the interview, a 4-page form, part of which was of identical questions both child and parent had to answer. The interviewer summarized her or his impression about the parentchild relationship and filled the “special problems” rubric with information he or she heard from the parent and the child, and the impression established during the interview.

The Instructors’ Evaluation at the End of the Semester

At the end of each one-semester “creative thinking” course, each instructor filled an evaluation form for all students. This form served for estimating the success level of the students as well as of the instructor.

This final evaluation included a “general success” rubric, which could be filled as following: “1” stood for “good”, “2” for “average” and “3” for “weak”. For this final evaluation the following 8 measures were taken into account:

- Thinking quality (original, adaptive, standard)

- Openness (extroverted/open, average, introverted)

- Social acceptability (leader, socially accepted, isolated)

- Self-confidence (high, average, low)

- Persistence (high, average, low)

- Attitude to problem-solving (active, average, passive)

- Direction of aggression (extroverted: cruel/hostile/ aggressive, depends on the circumstances, introverted: depression/submission)

- Involvement level in conversations (high, average, low).

Results

- Only 29 of the 100 examined students were girls. This rate was lower than in the cohorts of 1982, 1993, and 2003, Landau, & David [12]. It was also significantly much lower than among the 4.5-5.5-year-old age group both in 1993, when girls consisted of 42.5% and in 2003, when girls were 45.7% of kindergarten students.

- The mean age of girls-5.54 (Std=0.30)-was practically the same as that of boys-5.55 (Std=0.41)-among the kindergarten students studying at the Institute in 2003, David in press [11]. No significant age differences between pre-school girls and boys had been observed either in 1993 or in 2003. However, the mean age of both boys and girls in the 4.5-5.5 age group was significantly higher in 2004 than in 1993 (5.26, Std=0.33) and in 2003 (5.18, Std=.30) (ibid).

- Girls scored significantly lower than boys-p=0.02-in the total WSSPI results: 129.3 (Std=7.65) versus 133.3 (Std=7.78).

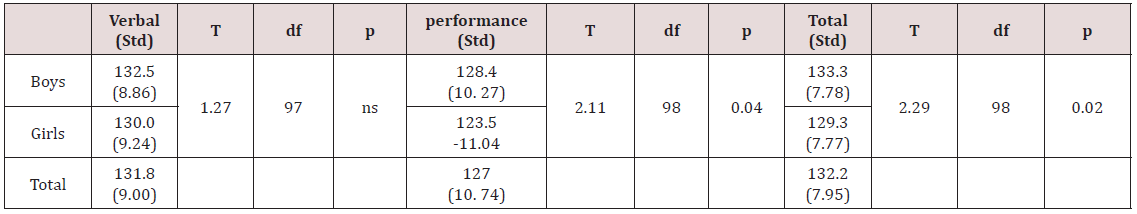

Let us see if these results were valid for the verbal and performance scores as well (Table 1). Boys outperformed girls in all 3 IQ measures: verbal, performance, and total. As expected, the largest and also significant difference was in the performance IQ; the difference in the total IQ was also significant but somewhat smaller than in the performance IQ.

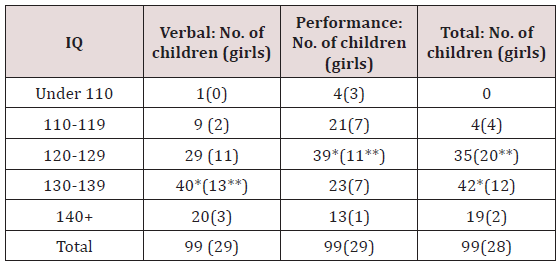

All boys that took the IQ exams successfully and received the interviewer recommendation were accepted to the Institute. On the other hand, the mean IQ of girls was lower than 130, usually the threshold for the Israeli minimal requirement for being referred to gifted programs. We shall hereby see if girls succeeded, according to their instructors’ evaluations, in a rate similar to boys’ in spite of their modest achievements in the cognitive abilities examination in comparison to boys. Let us compare the frequent value of each of the three IQ measures among boys and girls (Table 2). As can be observed from Table 2, while all distributions-of the verbal, performance, and total IQ of the children in our cohort were Gaussian, the frequent group of both the verbal and the total IQ was, as expected, in the 130-139 range, while for the performance IQ it was the 120-129 group. That was the case both for boys and girls. However, among girls only for the verbal IQ the frequent value was in the 130-139 range; both for the performance and the total IQ the frequent value was in the 120-129 range. Furthermore: only half of the girls had a total IQ of 130+.

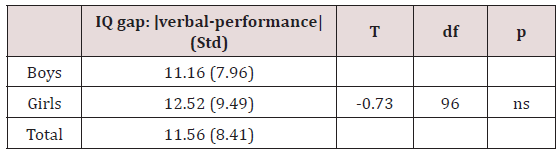

D. No gender differences were found in the magnitude of the gap between the mean verbal and performance IQ’s. Table 3 Shows the gender differences in the IQ gap. The mean gap between the verbal and the performance abilities of the children in our cohort was almost 12 points. Among regular students, a gap of 10 points is usually an indicator of low maturity level. Among gifted children, whose verbal abilities are at least 2 standard deviations above the norm, it is quite frequent to observe a gap of up to 10 points between these two abilities, and gaps of up to 15 points do not necessarily indicate that there is a need of psychological interference. In our cohort only 43 of the 98 children who had both their verbal and performance IQ measured had a gap of less than 10 points between these two scores. 26 more children had a gap of 11-15 points. For these children, consisting of almost a quarter of the cohort, one of the main aims of the “creative thinking” course was helping close the gap between these two abilities. Such a gap if left un-attended might widen, as is quite often observed in persons whose emotional and social development lags behinds their intellectual one.

Gaps of 16-40 points between the verbal and performance IQ had been observed among 28 of the children in our cohort. In cases of such a large gap professional observation is usually recommended in order to help them mature evenly. It should also be noted, that the correlation between the total IQ and the gap between the verbal and the performance IQs was less than 0.3. The correlation between verbal and the performance IQs gap and the verbal IQ was even smaller. The only larger than 0.3 correlation – that was also significant-that had been observed, was between verbal and the performance IQs gap and the performance IQ: -0.42 (P=0.01). This might indicate that many pre-school children who participated in the Institute’s activities were sent there as means to solve behavioral or emotional problems, and not necessarily just because of their curiosity, wish to learn more and the need to meet children with similar interests. This conclusion can also be made by calculating the rate of the children whose parents had reported special problems. Over 15% of the parents had reported visiting either an expert because of hearing/speaking problems, or a child development center due to behavioral, social or emotional problems.

E. No significant correlations were found between the total IQ score and any of the 9 success parameters. It should also be noted, that no significant correlation that reached the p=0.3 minimum had been found between the verbal or the performance IQ scores and any of the 8 components evaluated by the instructor. As expected, a large, significant (p=0.71) correlation was found between the total and the verbal IQ scores, and between the total and the performance IQ scores (p=0.75). However, the correlation between the verbal and the performance IQ scores was negligible.

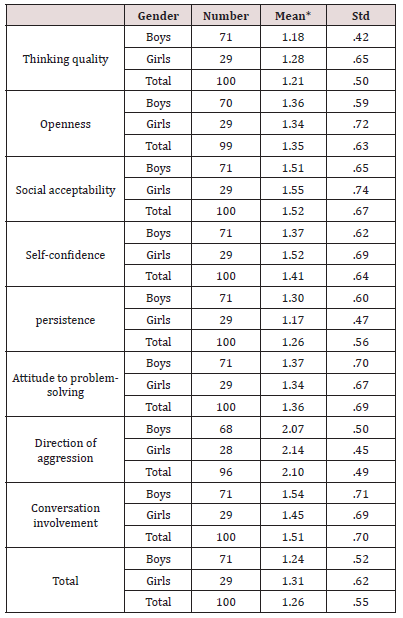

F. There were no significant gender differences either among the 8 parameters of the instructors’ evaluation or in the total “success evaluation” rubric based on those parameters as well as on the instructor’s opinion on the child’s performance, with a special focus on his or her development during the course. Table 4 Shows the rated means of boys and girls in each of those components as well as in the final evaluation. None of the findings in Table 4 reached the minimum level of significance. Boys outperformed girls in half of the parameters. The largest difference found was in the “self-confidence” component (0.15) (favoring boys). Girls got better evaluations in “persistence” (0.13), “conversation involvement” (0.09), “attitude to problem-solving” (0.03), and “openness” (0.02).

Discussion

The unexpected low rate of girls in the 2004 cohort of kindergarten children appears to be quite consistent with other findings of this study. It would be easy to assume that the low rate of girls was caused mainly because of parents’ perceptions of sex roles, found quite often even among parents of gifted families Anderson & Tollefson [15]; Hedges & Nowell [13]. However, in this cohort a substantial rate of the children who have participated in these 10 “creative thinking” courses have either enrolled at the Institute after being diagnosed as having some kind physical or emotional difficulty or have been identified during the interview as being at risk for familial or adaptation problems Goertzel V et al. [16], caused mostly by immaturity. 28 of the 100 students have had a gap of 16+points between their verbal and performance IQ scores, a difference that suggests uneven development. 10 of these students- 33%-were girls, the other 18-about 26%-boys. This difference, though not significant, might be caused by the fact that girls at this age are frequently more verbally- and socially developed than boys. It happens quite often that a girl who is still immature compensates for her immaturity by highly developed communication skills. Thus, it is likely that many parents experience difficulties with their very young gifted children, in most cases boys, and send them to the Institute hoping it would help their emotional growth. This assumption is also in accordance with the fact that the evaluation grades of the girls have not been better than those of boys. We might have expected that at least in the social-emotional characteristics, such as “openness”, “social acceptability”, and “involvement in conversations” girls would score significantly higher than boys, but that was not the case. It is possible that the kindergarten girls accepted to the Institute in 2004 were exceptionally immature in comparison to girls in this age group accepted in earlier years. It is also possible that unlike with boys, who were probably referred to the Institute mainly because of their high cognitive abilities, very talented girls who “caused no problems” did not, in most cases, start participation in the Institute’s activities. Another phenomenon that has to be of a great concern for educators as well as psychologists and counselors is the high rate of children - 25% - of those who had 16+point gap between the verbal and the performance IQ components, who have scored in the “gifted” rate in the performance component of the WSSPI exams but only “highaverage” or even “average” in the verbal part. A high verbal ability is usually an indicator for a high social potential, of good prospects to create and maintain social relations and good connections during the socialization process and afterwards. A child labeled as gifted usually uses these abilities to make friends, to mingle with others even when intellectually they are inferior to her or him. Lack of such verbal abilities might make the life of the gifted child much more complicated. One of the reasons for the comparatively low achievements of girls in our cohort might be connected to the direction of the “IQ’s-gap”: if such a gap appears more often among gifted boys than girls it is quite logical that the parents of these boys will notice their communication and social problems and be more willing to bring them to the Institute for giftedness identification [17-19].

The fact that no significant correlations were found between the total IQ score and any of the 9 success parameters evaluated by the instructors means that once a child has been accepted to the Institute, her or his success at the end of the first course depends on other causes ingredients rather than cognitive abilities.

The finding that the correlation between the verbal and the performance IQ scores were almost zero shows that in spite of the comparatively large gaps between the verbal and the performance IQ components, typical among the gifted with very high verbal abilities, a “new type” of the gifted child has to be taken into consideration regarding both research and education: The child with the high performance abilities but only average verbal ones. As we all know, verbal abilities in childhood are strongly connected to the amount and quality of verbal communication at home and among peers, much more than in educational settings. Further research is needed in order to investigate the phenomenon of the kindergarten gifted child whose verbal abilities are just average, in order to examine the implication of the future development of such a child and means to improve this situation.

Conclusion

The results of this study of pre-school children have exposed many findings that were unexpected, along with some expected ones. We should be cautious regarding some of them, while regarding others we must keep in mind that this is the first study done in Israel and one of the very few in the whole world that deals with connections between the level of cognitive abilities, as measured in the WSSPI exams, and the actual success in courses for the gifted. As such, more data is needed in order to re-test similar groups of children. We shall hereby summarize some of the limitations of this preliminary research and offer suggestions for further research.

Limitations

- The grading possibilities for the instructor’s evaluation were just “1”’ “2”, or “3”, which might limit the accuracy of the results.

- No unified control system for success evaluation has been applied, thus it might be that a child who got “1” by a certain instructor might have received “2” for similar performance by a second one.

- Kindergarten teachers, who have referred many children to the Institute, have not been questioned regarding their motives and criteria for recommending children as potential participants at the Institute’s activities. Thus, there are high prospects that many gifted children were not send for identification for giftedness.

Further Research is Needed

- A comparison between the characteristics of the children who finished the “creative thinking” course, those who were accepted to it but either did not enroll or dropped out, and those who were not accepted.

- Other exponents should be searched as well, not only to form a more complete picture of the characteristics of kindergarten students studying at the Institute but to help us understand findings and phenomena that have been remained unexplained.

- It is highly recommended that the children participating in this study will be re-studied for academic and social-psychological characteristics in the future, for enlarging the knowledge about connections between giftedness in the young age and materializing it in the future.

- The parents’ questionnaire should be expanded with at least one question about the motives of sending their child to giftedness exams. This information might help us be more accurate about the selection process which starts, at this age-group, at home; and perhaps understand better why the rate of girls has been so low.

References

- Rogers MT (1986) A comparative study of developmental traits of gifted and average youngsters. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Denver CO, USA.

- Smutny JF (1998) The young gifted child: Potential and promise an anthology. Cresskill NJ: Hampton Press, USA.

- Louis B, Lewis M (1992) Parental beliefs about giftedness in young children and their relation to actual ability level. Gifted Child Quarterly 36(1): 27-31.

- Robinson N M, Abbott R D, Berninger, Busse, Mukhopadhyay S (1997) Developmental changes in mathematically precocious young children: Longitudinal and gender effects. Gifted Child Quarterly 41(4): 145-158.

- Schneider BH, Daniel (1992) Peer acceptance and social play of gifted kindergarten children. Exceptionality 3(1): 17-29.

- Pfeiffer S, Petscher Y (2008) Identifying Young Gifted Children Using the Gifted Rating Scales–Preschool/Kindergarten Form. Gifted Child Quarterly 52(1): 19-29.

- Walsh RL (2014) Catering for the Needs of Intellectually Gifted Children in Early Childhood: Development and Evaluation of Questioning Strategies to Elicit Higher Order Thinking. Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Macquarie University NSW: Australia.

- David H (2012) Mathematical giftedness in early childhood. International Journal of Research in Management, Economics and Commerce 2(12): 19-31.

- David H (2013) Death ideation and suicide threats among young gifted children (Hebrew).

- David H (2017) Seeking help for young gifted children with emotional or educational problems: Who looks for counseling? Part I: Between the telephone call and the meeting. Journal for the Education Gifted Young Scientists 5(1): 57-70.

- David H (in press) The influence of students age on the identification for giftedness of girls: Findings in three decades cohorts.

- Landau E, David H (2005) Characteristics of gifted students: Age and gender Findings in three decades cohorts. Gifted education International 20(2): 138-154.

- Hedges L, Nowell A (1995) Sex differences in mental test scores, variability, and numbers of high-scoring individuals. Science 269(5220): 41-45.

- Ronald A, Spinath F M, Plomin R (2002) The aetiology of high cognitive ability in early childhood. High Ability Studies 13(2): 103-114.

- Anderson RW, Tollefson (1991) Do parents of gifted students emphasize sex role orientations for their sons and daughters? Roeper Review 13(3): 154-157.

- Goertzel V, Goertzel M, Goertzel T, Hansen A (2004) Cradles of Eminence: Childhoods of More than 700 Famous Men and Women (Second Edition). Great Potential Press, USA.

- Robinson N M, Abbott R D, Berninger, Busse (1996) Structure of abilities in math-precocious young children: Gender similarities and differences. Journal of Educational Psychology 88(2): 341-352.

- Schneider BH, Daniel (1992) Peer acceptance and social play of gifted kindergarten children. Exceptionality 3(1): 17-29.

- Smutny JF (1999) A Special Focus on Young Gifted Children. Roeper Review 21(3): 172-178.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...